What does it mean to be “good with money”? This phrase is used far more often than it is understood. Being good with money is a broad concept that extends beyond simply knowing how to save and invest. A healthy relationship with money requires us to know how to get it, keep it, grow it, save it, spend it, and give it away. Some might call it the ultimate balancing exercise.

An effective way to understand the proper balance and use of wealth is through the framework of a personal balance sheet. This common concept in the corporate world is also applicable at the family and individual level.

Just as companies have assets and liabilities, so will a personal balance sheet, although included assets and liabilities can be rather intangible. Making a personal balance sheet can introduce critical financial concepts and act as a great discussion starter that illuminates your financial goals, values, and beliefs. Here, we review the key components of a balance sheet, what they mean, and how to build your own.

A healthy relationship with money requires us to know how to get it, keep it, grow it, save it, spend it, and give it away. Some might call it the ultimate balancing exercise."

Let’s start with the basics: A personal balance sheet is an overall snapshot of a person’s wealth at a specific point in time that includes assets (what you own), liabilities (what you owe), and net worth (assets minus liabilities).

An asset is a store of wealth or anything that will create wealth in the future. The single most valuable asset on your balance sheet is your human capital – the theoretical value of a career’s worth of income. Examples of tangible assets include real estate, savings, retirement or investment accounts, jewelry or heirlooms, and direct business holdings.

The primary objective of saving and investing is to make sure that human capital successfully transitions to financial capital by the time you retire. Along the way, saving and investing can support other objectives as well, such as a down payment on a first home, advanced education, starting a business, raising kids, and philanthropy.

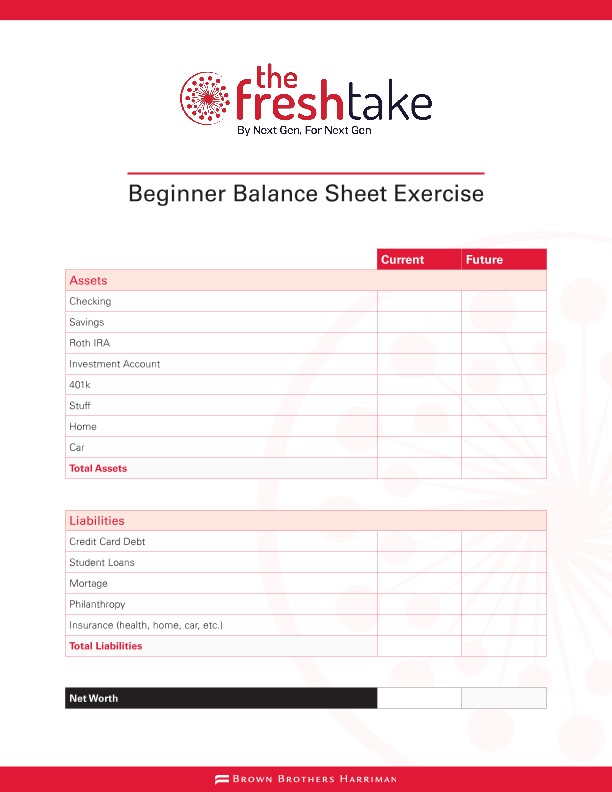

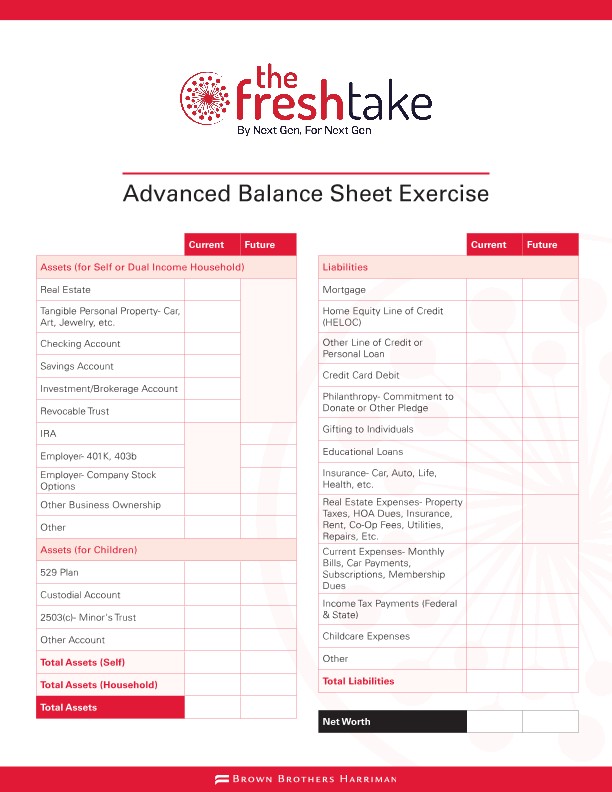

Just as an asset is anything that can generate wealth in the future, a liability is anything that may one day lay claim to that wealth. Examples include student loans, mortgages or rent payments, credit card debt, and taxes. Even philanthropy falls into the liability category when we adopt this broader definition. The personal balance sheet of a recent college graduate might look something like the below table.

Future assets and liabilities are often vague. The point of the exercise is not to determine the value of these assets and liabilities to the penny, but to demonstrate that wealth is a means to an end, where those ends are called liabilities for the sake of this framework.

This concept also reinforces the value of delayed gratification. This is often the earliest financial lesson for young children saving a meager allowance in anticipation of buying a coveted toy. The balance sheet concept extends that lesson across a lifetime of saving and investing, making explicit the transition of human into financial capital over time.

What's on your personal balance sheet?

During or immediately after college, your balance sheet may have more liabilities than assets (e.g., student loans), which is why it can be useful to also create an aspirational balance sheet for 10 or 20 years from now. Along with helping you plan for the future, a personal balance sheet expands on some core concepts of investing: asset allocation and risk.

Asset Allocation

Importantly, the balance sheet approach helps young investors to think robustly about asset allocation and how it should change over the course of a lifetime. As liabilities change (retirement, kids’ graduation, paying off a mortgage, etc.), asset allocation will likely change, too.

In theory, an investor’s strategic allocation shouldn’t change unless her liabilities do. That’s not to say that asset allocation should be set and then ignored.

On the contrary, robust asset allocation requires a continual assessment of shifts in spending, consumption, philanthropic interests, and lifestyle needs of the investor rather than a reaction to anticipated changes in capital markets.

[R]obust asset allocation requires a continual assessment of shifts in spending, consumption, philanthropic interests, and lifestyle needs of the investor rather than a reaction to anticipated changes in capital markets."

Risk

This approach also poses a novel definition of risk. Risk is traditionally understood as deviation from a benchmark, such as the S&P 500 index, or the possibility that a manager underperforms a passive index. Yet those definitions don’t reflect the ultimate objective of balancing assets and liabilities.

The personal balance sheet approach reminds us that real risk is that the balance sheet doesn’t balance: that liabilities are greater than expected, or that assets aren’t.

Understanding those risks leads to a further refinement of asset allocation where the risks to the liability side of the balance sheet help to inform how the asset side is structured. As an example, consider the risks that might threaten each side of a personal balance sheet:

Assets aren’t as great as anticipated… |

Liabilities or expenses are greater than anticipated… |

|

|

The spectrum of potential risk is as broad as our definitions of assets and liabilities. For example, if human capital is a significant asset on your balance sheet, then anything that might impair that value (unemployment or disability) is a risk.

Some of these balance sheet risks can and should be hedged through insurance: health and life insurance protects human capital, while home insurance protects housing assets.

Yet not all balance sheet risks can be hedged through insurance. It is important to consider the role that each asset class plays in addressing the risks to one’s balance sheet.

If liabilities such as tuition or mortgage payments have certain due dates, then something on the other side of the balance sheet should hedge against that “liquidity risk” by being in a liquid asset class.

Fixed-income assets usually play this liquidity role in a portfolio. Investment losses or fraud can be managed through effective manager selection and transparency.

Tax planning is essential to preserving assets and ensuring that liquidity is available once payments come due. None of this is a guarantee. Risk management is an exercise in identifying and mitigating risk, not a means of making it disappear.

Note that inflation appears in the above table as a risk to assets as well as liabilities. Inflation threatens to erode the real purchasing power of a dollar of assets while increasing the cost of future spending – and with current inflation rates remaining high, this is an important risk to monitor. The right allocations will differ from investor to investor and will evolve over time as liabilities and risks change.

Why build a personal balance sheet?

A personal balance sheet achieves a variety of objectives:

- It makes explicit the idea that wealth is a means to an end, whether these ends are quantifiable or subjective.

- It encourages a robust approach to asset allocation that takes into account individual risk profiles as opposed to anticipated market moves, as well as an understanding of the why and how of portfolio construction.

- It encompasses the various uses of wealth – saving, investing, spending, and philanthropy – that, in proper balance, make us good with money.

Considering the following questions when filling out your balance sheet can spark a meaningful discussion about your financial and personal goals and beliefs:

Now that you know what goes on a personal balance sheet, you can practice creating your own using the downloadable worksheets at the end of this article. |

These are just few questions that can spark an ongoing conversation about goals, values, and financial independence. If you are interested in learning more about the tools and exercises we provide to help the next generation as they assume control of wealth, please reach out for more details.

Contact Us

Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. (“BBH”) may be used to reference the company as a whole and/or its various subsidiaries generally. This material and any products or services may be issued or provided in multiple jurisdictions by duly authorized and regulated subsidiaries. This material is for general information and reference purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax or investment advice and is not intended as an offer to sell, or a solicitation to buy securities, services or investment products. Any reference to tax matters is not intended to be used, and may not be used, for purposes of avoiding penalties under the U.S. Internal Revenue Code, or other applicable tax regimes, or for promotion, marketing or recommendation to third parties. All information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy is not guaranteed, and reliance should not be placed on the information presented. This material may not be reproduced, copied or transmitted, or any of the content disclosed to third parties, without the permission of BBH. All trademarks and service marks included are the property of BBH or their respective owners. © Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. 2023. All rights reserved. PB-09101-2025-11-18